The ‘Secular AA’ Movement

In this blog post, Zachary Munro discusses the development of a non-religious recovery culture in Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), and how groups like Secular Organizations for Sobriety (SOS), and LifeRing Secular Recovery are renegotiating their relationships to AA’s origins in the evangelical “Oxford Group” of the 1930s. As this non-religious recovery culture grows, it continues to explore ways in which the Twelve Steps on the road from the “addicted-self” to the “recovering-self” might need neither God nor even “spiritual” discipline to work.

By Zachary Munro

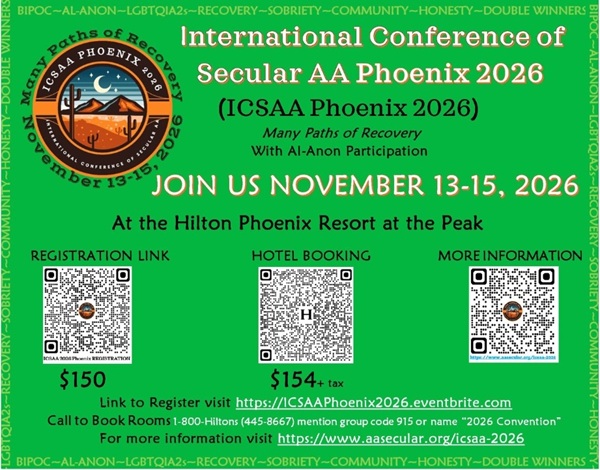

The religious components of Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and other Twelve-Step fellowships for addiction-recovery have long challenged the participation of secular individuals. The fellowship, which has a membership base of over two million, uses a spiritual program that emphasizes belief in a “higher power” and daily spiritual practice to achieve and sustain recovery. In recent years a growing secular movement has been occurring within AA that has prompted an increasing number of secular meeting groups to organize. This trend has seen significant growth since the early 2010s, supported largely through online networking websites such as AA Agnostica and AA Beyond Belief. The growth and increasing organization of this community has facilitated a culture centered on the experience of being secular in AA and navigating its spiritual program of recovery.

Popular references to the religious elements of AA are often accompanied by contentions over using a religious program for the treatment of a medical disorder. Internal debate over the religious elements has existed even within the fellowship since its inception in the late 1930s. [i]

AA emerged out of the Oxford Group, an Evangelical fellowship that had a reputation for helping alcoholics achieve sobriety. The Oxford Group treated chronic alcohol use as symptomatic of a spiritual sickness that could only be remedied by surrendering to God and living in accordance with the group’s religious principles. Among these principles are those that were gradually adapted into the less explicitly religious and more spiritually based Twelve Steps, six of which make reference to “God.”

Although AA does recognize Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD) to be a bio-medical disease, and was instrumental in popularizing the social understanding of addiction as disease, it continued the Oxford Group’s teaching that the condition is symptomatic of an underlying spiritual malady. The alcoholic is thought to suffer from a disordered or diseased self. Treatment is not to be found primarily in allopathic medicine but in working the program of spiritual disciplining, which involves reorienting and transforming the self to rehabilitate spiritual well-being. This includes attending group meetings which incorporate ritual practice, being in sponsorship, and working the Twelve Steps. The Steps are intended to produce a “spiritual awakening” and engender a transition from the addicted-self to the recovering-self.

In contradistinction not just to AA’s “God talk,” but also its “spiritual” model, a number of secular alternatives to AA have emerged, including Self-Management and Recovery Training (SMART), Secular Organizations for Sobriety (SOS), and LifeRing Secular Recovery. These and other programs tend to emphasize a scientific approach to treatment. Despite this fact, the secular movement occurring within AA has not been characterized by a simple rejection of either spiritual or theistic elements, but has produced dynamic forms of interaction with them.

If secularity emerges as a cultural form wherever people make meaning outside of organized religion, then for secular people in AA this happens not only by highlighting their differences with its religious and spiritual elements, but in the way these elements continue to inform how such individuals negotiate their participation in the program. In this way, the culture of secular AA is a “substantial” secularity, or what Lois Lee [ii] calls a “non-religious culture,” in that it defines itself in terms of its difference from the religious variant.

In the emerging body of popular literature on navigating AA as a secular person [iii], there are adapted versions of the Twelve-Steps accompanied by commentaries that articulate a non-religious understanding of the teaching and value of each Step. While such content illustrates the emergence of non-religion through codified approaches to the program, “Secular AA” meeting groups are sites for informal experimentation with developing a non-religious recovery culture.

The reproduction of traditional AA meeting formats maintains elements of the religious program like collective ritual action, personal confession, and an emphasis on self-transformation through particular forms of ethical self-disciplining. At the same time, open expressions of disbelief serve to undercut traditional norms of the meeting space and allow non-religious elements to emerge and incorporate themselves into the program in meaningful ways. For example, open expressions of a secular-self and how this identity informs the workings and experiences of recovery in AA, may serve to reconcile previous internal conflict that many have experienced due to the prevalent AA sentiment that they “need God” to work the program. Moreover, secular-self expressions provide pathways of identification between members with similar experiences, and for newcomers who have been put off of participating because of what they see as religious obstacles.

Through both formal recodifications of the program, such as adapted versions of the Twelve-Steps rid of theistic language, and informal assertions of secularity as a meaningful component of the recovering-self, Secular AA reconceptualizes the relationship between personal agency and various forms of power within the traditional AA model (such as the “Power greater than ourselves” that becomes the focus of recovery work as early as Step-Two in the original Twelve-Steps).

As my own research project on Secular AA develops, it will involve analyzing the significance of precisely these kinds of practices.

Whatever their particular logics and histories, they illustrate the potentials of resourceful borrowing and forms of positive interaction with religious cultures by non-religious cultures in order to aid personal and collective recovery. Moreover, for both researchers and those in recovery, developments occurring within the Secular AA movement are opening up space to explore the dynamics of interaction between religion and secularity beyond emphasizing forms of difference and opposition.

[i] For a historical chronology of this see: Kurtz, Ernest. 1979. Not-God: A History of Alcoholics Anonymous. Minnesota: Hazelden.

[ii] Lee, Lois. 2015. Recognizing the Non-religious: Reimagining the Secular. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[iii] For a few titles see: Cleveland, Martha. and Arlys, G. 2014, The Alternative 12 Steps: A Secular Guide to Recovery; Joe, C. 2013, Beyond Belief: Agnostic Musings for the 12 Step Life; Roger, C. 2015, Do Tell!: Stories by Atheists and Agnostics in AA.

Zachary Munro is a PhD candidate in the department of Sociology & Legal Studies at the University of Waterloo. He is currently undertaking fieldwork for his dissertation on secular people navigating personal recovery within Alcoholics Anonymous.

This is the official blog of the Nonreligion and Secularity Research Network. Its purpose is to provide a platform for the publication of short articles on a broad range of topical issues relevant to the academic study of nonreligion and secularism.

How very refreshing to have an “outside” viewpoint presented on our movement by a scientific researcher. And how fast things move today–in just a few years since the “movement” gained some traction, we are being written into history.

And speaking of history and religion, I’ve recently discovered an author, Yuval Noah Harari, who presents the most amazing secular view of history. His three books, Sapiens: A brief History of Humankind, Homo Deus: A brief History of Tomorrow, and 21 Lessons for the 21st Century, are absolutely illuminating in the way they portray a secular view of mankind and its early experimentation with that odd thing called religion. I recommend them highly for anyone interested in broader secularism, and our place in a secular universe.

Click on the image below and it will take you to his website:

Thank you Zach, though your article just barely scratches the surface. I look forward to more.And thank you Chris for the mention of those three books. Where do I find a bit of a review of them? (Haven’t visited the site Roger suggests yet.)

Shortly after I got sober, it occurred to me that if I were to go back to school and complete a PhD, you losers would have to call me “DOCTOR Bob!!” I would have liked that.

Carl Jung’s responded immediately to Bill Wilson’s 1961 letter. I find some interesting things in the letter:

Speaking of Rowland H–“His craving for alcohol was the equivalent on a low level of the spiritual thirst for being, expressed in MEDIEVAL LANGUAGE; the union with God.”

Re: the goal of achieving a “higher understanding” Jung wrote–“You might be led to that goal by an act of grace, OR through personal and honest contact with friends.” That sounds a lot like fellowship!!

I’m not dreadfully upset with the term “spiritual malady,” nor with AA’s religious roots. I see psychology lying beneath the religious language. I might dislike the term “spirituality,” but I’ll cop to “existential angst.” I firmly believe that my “problems” weren’t limited to drinking.

I am also fully convinced that “there’s more to quitting drinking than quitting drinking.” We HAVE to do something! That’s why there’s Refuge Recovery, and all the others. I think the exact mechanics are not terribly important. (Sorry, Thumpers)

A friend in California says we all get sober the same way; we just label it differently. Jung’s reference to “friends” suggests a solution lying in “connectivity.” That’s something that could be loosely labeled “spirituality,” for recovery purposes. Calling “union with God” medieval language strongly implies that the feeling is really something else.

Nice work, Zack.

Zachary,

IMHO, what we are fundamentally dealing with in recovery is, consciously or unconsciously, faith and belief, howsoever defined. The success of the AA model is fellowship, safety to share common addiction-related experience and adherence to commonly-shared guidelines – the Steps – as they may be modified to accommodate members shared felt sense of world-view. The beauty of a secular approach to sobriety is that it validates the wide diversity of objects of belief, the effectiveness of which is not dependent on a predetermined form. I would add that ‘belief’ here, as I intend it, can be synonymous with ‘acceptance’ of whatever format and reference materials a meeting may choose to use.

Thanks for your very carefully articulated post.

In Recovery,

Bob F.

Zachary,

I am interested in your statement that AA recognizes Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD) as a biomedical disease. About five years ago I asked AA’s General Service Office (GSO) whether they consider alcoholism to be a disease. They told me that the classification of alcoholism as a disease is an outside issue about which AA has no official opinion. AA literature uses terms like malady and illness, but not disease. While certain early members, especially Marty Mann, did much to promote the disease concept of alcoholism, as far as I know the fellowship itself did not and does not take this stance. Where did you get your information on this issue?

Dean W.

5 years ago I started taking serious inquiry into Karma and Reincarnation from a Buddhist perspective. It’s helped me alot.