Let’s Open Up About Addiction and Recovery

By Laura Hilgersnov

Originally published on November 4, 2017 in the New York Times

San Anselmo, Calif. — Fay Zenoff recently met a friend for dinner at a sushi restaurant in Sausalito, Calif. After they were seated, a waitress asked if they’d like wine with dinner. Her friend ordered sake. Ms. Zenoff declined. “Not for me,” she said. “I’m celebrating 10 years of sobriety this weekend.”

Because of the stigma attached to addiction, Ms. Zenoff, who is 50, took a risk speaking so openly. But when she and her friend finished eating, the waitress reappeared. This time she carried ice cream with a candle in it and was accompanied by fellow members of the restaurant staff. They stood beside Ms. Zenoff’s table, singing “Happy Birthday.” The evening, Ms. Zenoff recalled, was “just amazing.”

A victory, too. For 25 years, Ms. Zenoff, who began adult life with an M.B.A. from Northwestern, was an alcoholic who dabbled in heroin, Ecstasy and cocaine. “I felt so much shame about my past behavior,” she said, “that it was a huge hurdle to admit I was in recovery even to my family and friends.” It took three years for her to speak up among friends and another three for her to do so publicly.

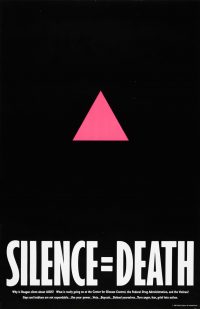

Now as executive director of the Center for Open Recovery, a Bay Area nonprofit, she’s promoting an idea considered radical in addiction circles: that people in recovery could be open and even celebrated for managing the disease that is plaguing our nation. She and other advocates believe that people in recovery could play a vital role in ending the addiction epidemic, much as the protest group Act Up did in the AIDS crisis.

It’s an idea that fits with the report released by President Trump’s opioid commission last week. Among the report’s 56 recommendations was a suggestion that the government battle stigma and other factors by partnering with private and nonprofit groups on a national media and educational campaign similar to those “launched during the AIDS public health crisis.”

Speaking up, however, carries real risk. People — especially doctors and pilots and others in similarly sensitive occupations — fear losing jobs, promotions and social standing if they admit they’re in recovery. The paradox is that stigma is most effectively dispelled through openness.

The need has never been greater. Approximately 21 million Americans (Facing Addiction in America) suffer from substance abuse. On average, 175 die from overdoses every day.

The need has never been greater. Approximately 21 million Americans (Facing Addiction in America) suffer from substance abuse. On average, 175 die from overdoses every day.

“People are dying who don’t need to die,” Ms. Zenoff said. “If it were safe for more people to say, ‘I’m in recovery,’ I think many more people could say, ‘I need help.’ ”

Other nonprofit groups, like Faces & Voices of Recovery in the District of Columbia, Facing Addiction in Connecticut, and Shatterproof in New York, are also encouraging the 23 million Americans in recovery to be more vocal. Even grieving families are growing more honest in obituaries, mentioning addiction as a cause of death with greater frequency.

This openness flies in the face of tradition. Since Alcoholics Anonymous was founded in 1935, anonymity has been the recovery community’s bedrock. In 12-step meetings, people identify themselves by first names only. Outside “the rooms,” they often don’t reveal that they are members of these programs at all.

As the mother of a young adult in recovery, I’ve seen the miracles these programs make possible. Anonymity creates a sense of safety that recovering addicts desperately need. Twelve-step programs save countless lives. There are many reasons not to tamper with them.

But I’ve also met men and women who are 20, even 30, years sober. They’ve overcome adversity and often trauma to live lives of courage, resilience and grace. I have seen their stories in “The Anonymous People,” a documentary directed by a co-founder of Facing Addiction, Greg Williams.

We need to hear more from them. There’s a way to share these stories while still honoring the traditions. In her work, Ms. Zenoff suggests people simply say, “I’m in recovery,” without identifying themselves as a member of A.A. or another 12-step program.

In fact, many recovering addicts are not in a traditional program. Some manage recovery independently. Others join Refuge Recovery, a program based on Buddhist principles, or Smart Recovery, which encourages reliance on self rather than a “higher power.”

No matter the path, why should they remain silent? “It’s like being a vegan but only being able to talk about it in a kitchen or a hospital,” Ms. Zenoff said, “or with another vegan.”

This spring, the Center for Open Recovery ran posters on San Francisco Muni buses, featuring vibrant people of all races, accompanied by the tagline “This Is Recovery.” For inspiration, the organization looked to the “Silence = Death” posters that raised awareness years earlier, encouraging openness despite the stigma.

This spring, the Center for Open Recovery ran posters on San Francisco Muni buses, featuring vibrant people of all races, accompanied by the tagline “This Is Recovery.” For inspiration, the organization looked to the “Silence = Death” posters that raised awareness years earlier, encouraging openness despite the stigma.

At the onset of the AIDS epidemic, many Americans blamed gay men for bringing the fatal disease upon themselves.

Unenlightened Americans today consider addiction a moral failing as well, one as likely to spur a trip to prison as to a treatment center.

“The Act Up marches, the AIDS quilt and the posters made people more sympathetic, and made gay people seem more human,” said Daniel Royles, an AIDS historian at Florida International University.

The activists shifted people’s understanding of the disease. After several years of pressure from people with AIDS and their supporters, to give one example, the federal Health Resources and Services Administration spending on AIDS programs increased more than thirteenfold in 1991, to $220.6 million from $16.5 million.

The government hasn’t yet done the same for addiction, even though this treatable disease kills more Americans every year than AIDS at its 1995 peak.

Consider how addiction compares with other diseases: In 2016, the National Institutes of Health devoted $5.6 billion to public research funding on cancer and $3 billion on AIDS. Substance abuse disorders received $1.6 billion, even though one-and-a-half times more people suffer from addiction than from all cancers combined. President Trump’s recent declaration of the opioid crisis as a “public health emergency” provided no immediate additional funding.

Despite the headlines, we’re still a nation in denial. According to Facing Addiction, one in three American households have a family member in active addiction, in recovery or lost to an overdose. But a survey by the organization also showed that nearly half of respondents weren’t convinced it’s an illness — despite a 2016 surgeon general’s report defining addiction as a “chronic neurological disorder.”

Jim Hood, Facing Addiction’s co-founder and chief executive, joked that addiction “is an illness that nobody is ever going to get, nobody ever has and nobody ever has had.”

People in active addiction — who can act in baffling ways — are perhaps less likely to change our perceptions of substance abusers. But what if addiction’s human face was your minister, who’d once struggled with heroin? Or your favorite college professor, who kicked a drinking habit and eventually earned her Ph.D.?

If Americans heard enough stories, would they clamor for more research funding and treatment beds then?

The decision to speak up is personal — and the stigma is real, especially in the workplace. It’s so pervasive that when Ms. Zenoff took over the Center for Open Recovery in 2014, her own board members, many in recovery, were reluctant to post their names on the organization’s website.

Stephen Simon, one of the funders behind the Center for Open Recovery, understands the hesitancy. The co-founder of a San Francisco investment firm and a member of the family that owns the Indiana Pacers basketball team, Mr. Simon, 51, has been sober for five years, after battling opioid painkillers. He’s open with his recovery privately, yet expressed “vulnerability” about speaking publicly. He agreed to be identified here only because of the staggering numbers of people suffering and dying.

“It’s so bad that I think anyone who’s been given a reprieve from the horrific nature of this disease should at least consider talking about it,” Mr. Simon said. “Maybe it will free up dollars or spur people with ideas and influence to bring an end to the epidemic. We can’t even measure what addiction is doing to the collective soul of the world.”

A link to a preview of the documentary The Anonymous People.

Interesting. I’ll celebrate 35 years this month and I definitely agree that we should open with our mentioning our sobriety and the absolute happiness and satisfaction we gain from sobriety… For a few years I’ve openly admitted to my history with alcohol and believe I’ve influenced several to begin their path to sobriety.

As a nurse in recovery (3.25 years!), I cannot expose myself as it would deleteriously affect my employability and cast suspicion on everything I handled as a nurse. I wish I could speak openly. The healthcare field is intolerant of addiction in its own members and quite judgmental. It’s a disease in others; a moral failing in providers. Unfortunate but I’ve seen, heard it, and even BEEN it before my own experience. Sad but true.

Hello,

The most unfortunate situation you’re in vis. your profession is a real fact in your working life. ALL decisions about disclosure/non-disclosure are completely your own and MUST be respected by all. I have come across several people in similar situations and the same unbreakable rule applies: all decisions surrounding disclosure are, and always will be, completely your own. Perhaps in time things will change but for now and for you anonymity is your chosen path.

As well, I’ve met many people with varying lengths of recovery who are totally open about their recovery. I am, fortunately, one of those.

I well remember the days early on in the aids epidemic (genocide?). The “Silence = death” campaign was very instrumental in forcing the issue onto the front pages. Something like that campaign is necessary with regard to addiction.

When I go to AA meetings now I always say “Hello, my name is Jack. I am a recovered addict,” And yes it pisses off the big book thumpers. But I’ve felt for a long time that anonymity for veterans might be something we should abandon. Newcomers and some professions are exempt of course.

Again, this is a decision I made for myself alone. All others, without any adverse judgement, make any decisions about disclosure if and when THEY choose.

Best to all,

Jack.

I appreciate your position. You have to do what feels right for you.

I can think of 4 physicians in my large men’s group, and a physician and a Nurse Practitioner or Physician’s Assistant – I can’t keep them straight – in my small group. Pretty much all of them were forced into recovery by their regulating boards; all but one, who’s retired, are still working. I’ve known a number of nurses in the past including a full professor at a top-20 nursing school. I don’t attend lawyers-only meetings for reasons I’ll be happy to share if anyone cares but I’d suggest to Esse that she see if she can find a Caduceus meeting or another medical professionals-only meeting.

Good advice Tim.

I know two men who are professional drivers that started a “drivers only” meeting. Membership is by one driver bringing another to a meeting. Names are not used. It works for them.

Jk.

For the nurse who commented… I understand; some can speak freely, others, like you, can not. I attend an agnostics meeting where we have at least three from medical professions… perhaps you can find others in such meetings and benefit from their experiences.

32 years, and like many others here, I’m fairly open about it. Among other things, I kept a Big Book with the dust jacket on in my “back desk” in my federal law office where it was easily seen by anyone who I was meeting with. Of course, many of them had known me when I was working drunk and when I went off to Hazelden, so few secrets anyway.

I’ve been very open about my addiction since 1970.

As a result I’ve been able to “educate” numerous doctors about our addiction disease. (I’ve filled in blanks of things they should have learned in MD school.)

When I got sober years ago Blue Cross had a movie on TV “The Unknown American” – about addiction as a medical issue. Any one remember this?

This led me to question why all the God emphasis in a recovery from this illness.

Marnin

I have been sober for thirty-seven years. As I understand it, AA does not discourage openness about recovery, but does ask that people remain anonymous concerning their membership in AA. Two reasons: if they drink again, it will give some the impression that The AA program “doesn’t work” and secondly that it can be an excellent exercise in humility for most alcoholics who seem to need to make an effort to curb the ego a bit.

In all closed meetings and some open meetings I say my full name. I hand out my personal card with my full name and phone number to newcomers. I think it was Dr Bob who warned about being “too anonymous.” When I was still working (now retired) I started opening up to coworkers after about 10 years of sobriety. Had many opportunities to share my story because of that. Even took an HR director who was in a bad relationship with an alcoholic to her first Al Anon meeting.

There are times when for personal reasons we cannot be open about our recovery. But if we always remain in the background, we may be keeping the solution hidden from someone who needs help.

I declared “honesty” as being my “higher power” when I first attended meetings – now I recognize it as the group. I’m single and 67, have had a few “dates” from various websites where “never drink” is on my profile. Should the first coffee meeting go well I always tell the person that I go to meetings. In today’s “wine tasting” culture, you might be able to imagine that there are few choices for a non-drinking atheist!!

Nevertheless, honesty is always the best policy!

In a similar demographic, I am discouraged at the militant nature of those dedicated to spending their golden years constantly intoxicated. In a state with legal MMJ, many potential dates are too stoned to even drive. (“Swing by…”) Throw in peers with medical reasons to be zonked on pain meds, and it’s hard to find sober company, M/F, at all. Much less finding a date… I have no intention of “fouling the nest” by getting involved with regulars at the meeting I go to, so… Still single. I wonder if young people have any idea how really bombed a great number of Seniors are!

An excellent article, Roger. Thanks for reprinting it here.

I have questioned the relevance of anonymity in AA in the 21st Century. It is especially irrelevant among younger folks. It and the so-called “singleness of purpose” issue, to my mind, are 20th Century concepts that may become more and more irrelevant during the 21st Century.

Good point. In my opinion being in recovery should be something to be proud of, not ashamed of. I am open about it in my personal life. However, anonymity should always be respected for those who desire it. As for the “singleness of purpose”, don’t get me started. That made me feel unwelcome as a newcomer with multiple addictions. How many alcoholics have not at least dabbled in other substances (aka “outside issues”), especially those of us born after 1950?

Hi Hilary. You’re so right!!

The chances of a newcomer, born after about 1960, being addicted to just one intoxicant is in my experience just about nil. The “singleness of purpose” crowd are dangerously wrong and can collectively take a hike as far as I’m concerned.

Cheers,

Jack.

Evan “A.A. #2” (Dr. Bob) talks about his use of sedatives in his story (“Dr. Bob’s Nightmare”). And the story (“Acceptance is the Answer”) that includes the page most of our sponsors have told us to read (page 417 in the 4th edition) tells about heavy use of pharmaceutical drugs in addition to alcohol. I’ve never understood the reasoning for a prohibition of any mention of drug use in AA meetings. To pretend that drug use has no relationship with alcohol abuse is tantamount to writing a death warrant for many of our newcomers.

AA says it is a program of attraction, not promotion. It is hard to attract people if we are wearing camouflage, they can’t see us. I have been free from drugs and alcohol for 45 years and for the past 35 have at first been very open and secondly an advocate for the joys of life in recovery for the past 20 or so. I have had a TV series teaching about substance use disorder and recovery and worked on NRAC (National Recovery Advisory Committee) and in both those venues being open about being in recovery allows people to see options other than a life that is “dull, boring and glum”. We need to shine a light so that people can see and want what we have. This can be done without interferring with the tradition of anonymity.

Totally agree with you Rand! Thank you!!

The following two assertions appear fairly early in this article: (i) “Approximately 21 million Americans (Facing Addiction in America) suffer from substance abuse.” and (ii) “Other nonprofit groups, like Faces & Voices of Recovery in the District of Columbia, Facing Addiction in Connecticut, and Shatterproof in New York, are also encouraging the 23 million Americans in recovery to be more vocal.”

More Americans are “in recovery” than are actually suffering from it?

I think this is a problem of conflating anonymity in terms of – specifically – membership in Alcoholics Anonymous and of being in recovery. I freely and publicly speak of my sobriety and identify as a long-term member of the recovery community. No breach of any traditions. I will not mention our fellowship, nor would I be helping people get to recovery if I did. Too often when someone writes anything about AA, the haters pile on with astonishing vituperation.

I speak quite openly about being in recovery now. In the past – before obamacare – I had to lie on all health care forms I filled out, and then tell doctors “I’m an alcoholic in recovery BUT DON’T WRITE IT DOWN” – just for the sake of not jeopardizing my health insurance – where I paid $700 per month and still had to pay for everything myself because of a $10,000 deductible – is that crazy or what? Admittedly it is difficult to talk about this without starting to talk politics – another taboo in AA, though that one has some merit – if we start talking politics, we are likely to fall apart in sectarian political squabbles – and yet, alcoholism is of course a political, social problem, not just an individual one.

Anyway – yes, we do need to let it be known that we are in recovery. I keep thinking of the day when my increasing openness will land me in trouble with some 30 year old desk-wallah, and I have to meekly refrain from saying “yeah, I have been sober since before you were born”.

Or the time I was hauling a van full of people home from an AA meeting – they were sitting on makeshift seats in the back, and I got stopped by a highway patrol officer not much older than that, and when he asked what we were doing I told him we were on our way home from an AA meeting, and he answered “do you have any drugs in there?”, and it was all I could do to refrain from insulting him to the best of my considerable ability. Might as well have, since he gave us all tickets anyway for not having seat belts on the milk crates. I did go to court and told the judge I hoped they appreciated my hauling AA people around, and their going to meetings and all, and that I hoped he would dismiss the tickets, but he just knocked off 50 bucks. There is of course a fine line here of trying to trade on AA reputation – which can in general be an issue with the topic at hand, that once we are not anonymous we can try get special favors out of it. But probably that is less of an issue than the stigma we have to endure. Lots of those, like “former smoker” (30 years ago), “divorced” (35 years ago), “alcohol abuser” (30 years ago).

But I guess it is also a problem that AA broadcasts the opinion of “once an alcoholic, always an alcoholic”, even if it is for the most part true, but it does contribute to the societal stigma. You see a lot of questions on forms like “Have you ever had a problem with alcohol or drugs”, which can keep you from crossing borders, get health insurance, buy guns, get certain jobs. But to the extent some of us are safe from the repercussions of this stigma, we need to speak up for the sake of those who aren’t.

Thanks life-j, you’ve reminded me to be grateful that I live in Canada.

There are plenty aspects of AA that might be improved. I do not agree that the spirit of anonymity as it is practiced in AA is among them. The anonymity that AA embraces is twofold: We are free to reveal anything we like about ourselves to whomever we choose but we are asked not to reveal the identities or share personal stories of other members. We also are asked not to publicize our affiliation with AA at the level of press, radio and films. Neither of these principles has prevented common knowledge of what AA is, how we can be found and what we do from becoming common knowledge. AA meetings are routinely well portrayed in movies and on television. AA has become a well known cultural element. We occupy exactly the niche in our society that was intended by the original founders. When people are confronted with problems of addiction we discover our friends, colleagues and medical professionals routinely suggest that we consider AA or other twelve step programs. As comments here have already suggested there is no hesitance among many members to reveal our recovery when we find it to be appropriate. In fact, we already are “Opening Up” about addiction.

I appreciate the accuracy of this comment as I do the opinions of others in this chain. Only thing I might add is that the spirit of anonymity extends to being a “worker among workers,” thus working toward a level of humility that may be synonymous with modesty about our progress in recovery or an “accurate perception of who we really are coupled with a sincere desire” to improve.

I’ve been sober for over 20 years and have been “out” since day 1. In so doing, I discovered employers who were in recovery, or who had family members that were and it’s never been an “issue”. Today, I work in substance misuse here in the UK, so being “out” to colleagues is not an issue and the charity for which I work actively encourages people in recovery to work for them.

My understanding of the tradition is that we’re suggested to be anonymouse AT the level of press, radio and film. Below that level, there is no suggestion that we should remain anonymous.

32 years, and like many others here, I’m fairly open about it. Among other things, I kept a Big Book with the dust jacket on in my “back desk” in my federal law office where it was easily seen by anyone who I was meeting with. Of course, many of them had known me when I was working drunk and when I went off to Hazelden, so few secrets remained anyway. I wonder how many folks carefully guard their anonymity and the put Keep It Simple or circle-and-triangle decals on their cars.

Except for one hugely embarrassing miscommunication with a reporter doing a story about me, I’ve always worked to be anonymous “at the level of press, radio and film,” about AA, not necessarily about being sober.

I agree with most of the article; however, what is often stigmatizing is not the “disease” itself but the behaviors that accompany it.

A reason for anonymity that also circulates is protection of AA program; if a member makes public her involvement with AA and ends up not staying sober, AA takes a hit. The logic being that the “fault” is not programmatic but individual. I don’t agree with this logic, as I think we look for all possible means to facilitate recovery, even if that means making changes to the traditions to meet the needs of those looking for help.

Hi all. This is my 1st contribution on here. I read the article a couple of days prior to it hitting this site, it resonated quite strongly with me, thus I feel compelled to add my voice.

I am a gay man. 50. Approaching 2 years free from my addictions.

I felt as though I were coming out of the closet, albeit an entirely different one, all over again. It was decades ago that I came out in regards to my sexual orientation.

I agree wholeheartedly with the premise of the article that it is healthy to be out and open about who we are. This openness is absolutely crucial for others to know that they are not alone in their struggle. Perhaps if more people were upfront in regards to their recovery, addiction wouldn’t carry such a stigma. Newcomers just might seek out help sooner.

Now the flip side is that ‘coming out’ as an addict/alcoholic may be exceptionally helpful to the individual doing so. I spent a couple of decades lying/deceiving/analyzing every single correspondence with others in order to conceal my true sexual identity. This is so unhealthy mentally. Anxiety!!! ‘what if I slip up and my true self is exposed?’ It is my strong belief that this greatly contributed to my personal mental health issues and concurrent addiction.

Bottom line is that it can be a scary and emotional thing to be so open about an intensely private part of our lives, however, in my opinion it is so incredibly freeing and reduces the anxiety level immensely.

Recognizing that this is an individual choice, and that circumstances should always dictate that one feels safe in coming out, always. We benefit and we can be a benefit to others. I couldn’t recommend it more.

Thank you, Andrew. Thinking of a struggle to avoid being found out as an alcoholic, your story reminds me very strongly of the days when gay people often felt compelled to use gender-neutral pronouns, something that must have been, as you describe, terribly hard and also tended to suggest the very thing the speaker was trying to hide. Being in the closet, whether as a gay person or as an alcoholic or as an atheist is hard work.

I was open about my sobriety with family, friends, and co-workers from the beginning, and like you, Laura, I had positive experiences as a result. The moments that really stick with me are those with people not yet in recovery, who see my recovery as a sign of hope for themselves. I am fortunate that my profession is mostly free of addiction stigma; if I had been in the medical, teaching, legal, or law enforcement fields, I would not have been as open. In addition, I was in my early twenties when I got sober. The stigma is less for the young; those who judge addiction as a moral failing are more likely to “forgive” addiction as a “poor choice” made when I “didn’t know any better.”

I have always interpreted AA anonymity as twofold: 1) do not repeat things said by others in meetings outside of meetings; 2) do not present yourself in public as an AA spokesperson or AA guru. That’s it.

I have been sober in AA for 33 years – continuous sobriety.

I have used my first and LAST name since day one because I figured that is who I am and the two names (married) just went together. At the time of course I was in the minority (Still am in a big way) but also noticed right away that some of the people I considered “winners” did this also.

Sally Kellis

I started using my entire name this last time around, after 7 years of in and out. I have also been very open about being an alcoholic. For me, hiding the fact I was alcoholic was a way to leave the door open to possible drinking. Recently I mentioned in a job interview that I was 29 years sober, and I got the job! I needed to stop hiding, but that was my personal choice.