Anonymity in the 21st Century

By bob k

A Nameless Group of Drunks

In the 1930s the whole concept of “anonymity” was very simple.

Bill Wilson’s “nameless group of drunks”, helping themselves by helping each other, were progressing into unprecedented months, and even years of sobriety. The admission of alcoholism, so vital to recovery, could, at a public level, bring career and social consequences, as devastating as those from active drinking. It was vital that “prospects” be able to come and try this new therapy with the explicit assurance that they could do so with absolute confidentiality. Wilson recounts for us the thoughts of this time period:

Anonymity was not born of confidence; it was the child of our early fears. Our first nameless groups of alcoholics were secret societies. New prospects could find us only through a few trusted friends. The bare hint of publicity, even for our work, shocked us. Though ex-drinkers, we still thought we had to hide from public distrust and contempt.

When the Big Book appeared in 1939, we called it “Alcoholics Anonymous.” Its foreword made this revealing statement: “It is important that we remain anonymous because we are too few, at present, to handle the overwhelming number of personal appeals which may result from this publication. Being mostly business and professional folk, we could not well carry on our occupations in such an event.” Between these lines, it is easy to read our fear that large numbers of incoming people might break our anonymity wide open. (Twelve and Twelve, pp. 184-5)

The actual impact of the book was initially crushingly disappointing, but tremendous growth did come, albeit somewhat later. The earliest anonymity concerns were the least complex, and the most important. “Clearly, every AA member’s name – and story too – had to be confidential, if he wished.” (Twelve and Twelve, p. 185) Though the social stigma attached to alcoholism has diminished significantly, each person’s right to decide his own level of privacy remains paramount. As the new society experienced explosive growth in the early forties, lessons were learned, and the initial simple “anonymity” idea morphed into a broader “tradition”, incorporating principles of humility, unity, equality, sacrifice, and responsibility.

The Yellow Card

The “Yellow Card” is read at many meetings: “Who you see here, what you hear here, when you leave here, let it stay here”.

In the early days of AA, when more stigma was attached to the term “alcoholic” than is the case today, this reluctance to be identified – and publicised – was easy to understand. As the Fellowship grew, we came to realize also that many problem drinkers might hesitate to turn to us for help if they thought their problem might be discussed publicly, even inadvertently, by others; and that much of our relative effectiveness in working with alcoholics might be impaired if we sought or accepted public recognition. (Alcoholics Anonymous in Devon)

The Oxford Group

Several reasons propelled the “nameless group of drunks” to disassociate themselves from the Oxford Group. One motivation involved the contradictory views of the two societies regarding publicity:

Because of the stigma then attached to the condition, most alcoholics wanted to be anonymous. We were afraid also of developing erratic public characters who, through broken anonymity, might get drunk in public and so destroy confidence in us. The Oxford Group, on the contrary, depended very much upon the use of prominent names—something that was doubtless all right for them but mighty hazardous for us. (AA Comes Of Age, p. 75)

The Cleveland Indians

The eyes of America were firmly fixed on the sport of baseball in 1940. It was a way of celebrating an economic recovery that had been such a long time coming, and it provided a distraction from the escalating problems in Europe. Baseball excitement was especially feverish in Cleveland, Ohio, where Indians’ fans were electrified by the performances of future Hall of Famer, “Bullet” Bob Feller. The Iowa farm boy had pitched his first game in 1936 at the age of seventeen, and struck out an astonishing fifteen batters. To provide guidance and support to Feller, the team’s manager and owner hired an experienced catcher, and an alcoholic, Rollie Hemsley.

Hemsley had talent and experience with a variety of teams. However, “wherever he had played, the catcher’s bizarre behavior revealed him to be the team drunk.” (Ernest Kurtz, Not-God: A History of Alcoholics Anonymous, p. 86) Rollie Hemsley’s fame as personal catcher, and mentor to the young “phenom”, exponentially escalated on opening day of the 1940 season when he caught Feller’s no-hitter.

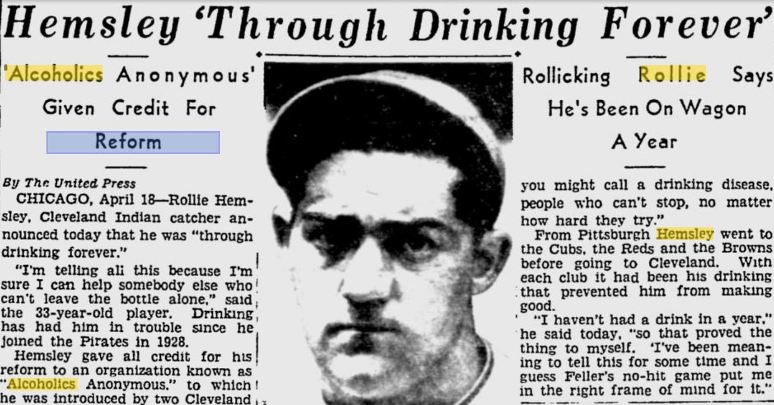

In a Chicago hotel news conference of 16 April 1940, Rollie Hemsley, erratic star catcher for the Cleveland Indians baseball team, announced that his past eccentric behavior on and off the diamond had been due to “booze,” that he was an alcoholic who had been dry now for one year “with the help of and through Alcoholics Anonymous.” (Not-God, p. 85) Newspaper stories about this event were sensational and they brought in many new prospects. Nevertheless this development was one of the first to arouse deep concern about our personal anonymity at the top public level. (AA Comes of Age, pp. 24-5)

The Hemsley publicity continued, and it was nationwide. Although not always decorous, the exposure was effective in drawing problem drinkers into AA. Hemsley’s status as a “spokesperson” for AA provoked a reaction in Bill Wilson: certainly jealousy, and perhaps a bit of resentment. “Soon I was on the road, happily handing out personal interviews and pictures”, Bill wrote. “To my delight, I found I could hit the front pages, just as he could. Besides he couldn’t hold his publicity pace, but I could hold mine… For two or three years I guess I was AA’s number one anonymity breaker.” In fact, Wilson may have over-sold his own misbehavior “to illustrate how baser human emotions such as competitiveness and envy can be disguised as motives of altruism and desire for the highest good.” (Pass It On, pp. 237-38)

The Hemsley publicity continued, and it was nationwide. Although not always decorous, the exposure was effective in drawing problem drinkers into AA. Hemsley’s status as a “spokesperson” for AA provoked a reaction in Bill Wilson: certainly jealousy, and perhaps a bit of resentment. “Soon I was on the road, happily handing out personal interviews and pictures”, Bill wrote. “To my delight, I found I could hit the front pages, just as he could. Besides he couldn’t hold his publicity pace, but I could hold mine… For two or three years I guess I was AA’s number one anonymity breaker.” In fact, Wilson may have over-sold his own misbehavior “to illustrate how baser human emotions such as competitiveness and envy can be disguised as motives of altruism and desire for the highest good.” (Pass It On, pp. 237-38)

Explosive Growth in Cleveland

Cleveland had become the hot-bed of AA, six months prior to the Hemsley media hype, and that had everything to do with a series of articles in the local newspaper, the Cleveland Plain Dealer.

Clarence Snyder was the driving force behind the phenomenon that was Cleveland AA. A highly successful car salesman, Clarence had skills that were the result of hard work and very innovative marketing approaches. He brought these skills to AA, and was an aggressive recruiter and a publicity seeker. Clarence told everyone that Elrick B. Davis, a reporter from the Cleveland Plain Dealer, had been plunked off a bar stool and was attending AA meetings “as a customer”. But was he?

According to early member, Warren C., “Clarence sneaked a Plain Dealer reporter into one of the meetings. He posed as an alcoholic. He wasn’t really. He was a writer…. Whatever his status, the articles Davis wrote set off an unprecedented wave of growth for AA in the Cleveland area.”

On 21 October 1939, Cleveland’s most prestigious newspaper, the Plain Dealer, published the first of an editorially supported series of seven articles by reporter Elrick B. Davis. Both the articles and the editorials calmly and approvingly described Alcoholics Anonymous, emphasizing the reasonable hope this new society held out to otherwise hopeless drunks. (Not-God, p.84)

As Bill described the series: “In effect the Plain Dealer was saying, ‘Alcoholics Anonymous is good, and it works. Come and get it’”. Hundreds did; by the following year, the city had 20 to 30 groups and several hundred members. Said Bill, “Their results were… so good, and AA’s membership elsewhere… so small, that many a Clevelander really thought AA had started there in the first place”. (Pass It On, p. 224)

Clarence, Rollie, & Marty – Beneficial Breaches

The story of Rollie Hemsley, recounted in detail above, was used as evidence of the danger of a public relations policy which employs “promotion”, i.e. celebrity endorsement. Without debating its reality as a problem, there were unquestionable corresponding benefits. Hundreds of thousands of people came to know of the existence of Alcoholics Anonymous as the result of the Hemsley interviews, and it is unimaginable that this celebrity endorsement did not lead to a significant spike in membership numbers and sales of the Big Book.

The most dramatic positive outcomes EVER produced by an anonymity breach, were those that resulted from Mrs. Marty Mann going public as a person who had recovered from alcoholism through participation in AA. This tale was told in some detail a week ago on this website (Marty Mann and the Early Women of AA). Tremendous benefits came from disregarding AA’s pro-anonymity position, a stance which had recently been codified. With the blessing of Bill Wilson himself, the opposite of our “official policy” was done to “serve the greater good.” Clarence Snyder had taken it upon himself to do the same seven years earlier, with the Cleveland Plain Dealer. The explosive growth of AA in Cleveland witnesses the upside to his “wrong” actions.

The 12 Traditions

Everywhere there arose threatening questions of membership, money, personal relations, public relations, management of groups, clubs, and scores of other perplexities. It was out of this vast welter of explosive experience that AA’s Twelve Traditions were first published in 1946 and later confirmed at AA’s First International Convention, held at Cleveland in 1950. (Twelve & Twelve, p. 18)

These then are the long form traditions developed in the early years of AA that deal with the issue of anonymity. “Our AA experience has taught us that”:

Tradition Eleven. Our relations with the general public should be characterized by personal anonymity. We think AA ought to avoid sensational advertising. Our names and pictures as AA members ought not be broadcast, filmed, or publicly printed. Our public relations should be guided by the principle of attraction rather than promotion. There is never need to praise ourselves. We feel it better to let our friends recommend us.

Tradition Twelve. And finally, we of Alcoholics Anonymous believe that the principle of anonymity has immense spiritual significance. It reminds us that we are to place principles before personalities; that we are actually to practice a genuine humility. This to the end that our great blessings may never spoil us; that we shall forever live in thankful contemplation of Him who presides over us all.

Anonymity in the 21st Century

The stories of Marty Mann, Clarence Snyder, and “Rollicking Rollie” Hemsley have specific relevance to the recovery world of 2013. That there has been a recent spate of anonymity breaches by celebrities is nothing new, but of late, AA’s very principles of anonymity themselves have been called to question. David Colman, a writer for the New York Times, broke his own anonymity as a 15 year sober member of Alcoholics Anonymous, with the May 6, 2011 article “Challenging the Second ‘A’ in AA”: “More and more anonymity is seeming like an anachronistic vestige of the Great Depression, when AA got started and when alcoholism was seen as not just a weakness, but a disgrace.”

Colman then lists a few of the numerous memoirs of recent years from recovered/recovering 12 steppers from Eric Clapton and Nikki Sixx to Nic Scheff and Augusten Burroughs. James Frey’s “A Million Little Pieces”, fabricated in part though it was, took an significant segment of the North American public to the worlds of addiction, treatment, and Oprah. Ironically, Frey is not an anonymity breaker from AA’s perspective as he rejected AA, and is not a member.

Eminem (“Recovery”) and Pink (“Sober”) have been very public about their enthusiasm for sober living which they achieved and sustain through participation in 12 Step recovery. “I think it’s extremely healthy that anonymity is fading”, says Clancy Martin, a philosophy professor at the University of Missouri, who had recently broke his own anonymity in “Harper’s” magazine.

Eminem (“Recovery”) and Pink (“Sober”) have been very public about their enthusiasm for sober living which they achieved and sustain through participation in 12 Step recovery. “I think it’s extremely healthy that anonymity is fading”, says Clancy Martin, a philosophy professor at the University of Missouri, who had recently broke his own anonymity in “Harper’s” magazine.

The violations by ordinary members of Facebook, and other social media, are legion. Maer Roshan’s excitement about sobriety led to his becoming editor of The Fix, a Web magazine directed at the recovery world. “Having to deny your participation in a program that is helping your life doesn’t make sense to me”, he offers. Author and AA member Susan Cheever wrote an essay in “The Fix” entitled “Is It Time to Take the Anonymous Out of AA?” She writes, “We are in the midst of a public health crisis when it comes to understanding and treating addiction“. She’s sees AA’s anonymity policies as contributing to the public’s lack of insight into these problems and their solution.

Congressmen Patrick Kennedy and Jim Ramstad acknowledged their own membership in AA while actively campaigning for a bill to get insurance companies to provide better coverage for addiction treatment. “The personal identification that Jim and I brought to this issue as recovering alcoholics gave us a place from which to speak about this. Stigma here is our biggest barrier, and knowledge and understanding are the antidote to stigma.”

Comedian and late night talk show host, Craig Ferguson, on the occasion of his 15th year sobriety anniversary, talked for about ten minutes about his addiction and recovery from alcoholism. Without explicitly saying that he was a member of Alcoholics Anonymous, he cleverly and clearly made the disclosure advising anyone with a problem with alcohol to seek help from an tremendous organization that is listed “at the front of the phone book, the VERY front!” Years before, a different celebrity told Johnny Carson that “he was attending a 12 Step program that dealt with alcohol”.

Such word games are addressed by Cheever. “I am increasingly uncomfortable with the level of dishonesty. This dancing around and hedging, figuring out ways of saying it that aren’t saying it… all the ‘code words.’ I am sure this is not what Bill intended.”

My name is Roger, and I’m an alcoholic

Chicago Sun-Times film critic and television personality, Roger Ebert, died Thursday, April 4, 2013, ending a lengthy battle with cancer. On August 25, 2009, Ebert had gone very public in a well-read blog – My name is Roger, and I’m an alcoholic – about his “other” disease, alcoholism, and his 30 years of recovery as a member of Alcoholics Anonymous. (Friends from Chicago assure me that he was a real member, and a good one.) The blog, of course, is a horrendous violation of AA’s eleventh tradition, but it is done magnificently – a glowing tribute to Alcoholics Anonymous. The piece is well-written, respectful, accurate, and dripping with gratitude. I see NO attempt at self-aggrandizement or attention-seeking.

Chicago Sun-Times film critic and television personality, Roger Ebert, died Thursday, April 4, 2013, ending a lengthy battle with cancer. On August 25, 2009, Ebert had gone very public in a well-read blog – My name is Roger, and I’m an alcoholic – about his “other” disease, alcoholism, and his 30 years of recovery as a member of Alcoholics Anonymous. (Friends from Chicago assure me that he was a real member, and a good one.) The blog, of course, is a horrendous violation of AA’s eleventh tradition, but it is done magnificently – a glowing tribute to Alcoholics Anonymous. The piece is well-written, respectful, accurate, and dripping with gratitude. I see NO attempt at self-aggrandizement or attention-seeking.

This is a “good-bye letter” from a dying man.

Here are Ebert’s own words in answer to the obvious question.

You may be wondering, in fact, why I’m violating the AA policy of anonymity and outing myself. AA is anonymous not because of shame but because of prudence; people who go public with their newly-found sobriety have an alarming tendency to relapse. Case studies: those pathetic celebrities who check into rehab and hold a press conference.

In my case, I haven’t taken a drink for 30 years, and this is God’s truth: Since the first AA meeting I attended, I have never wanted to. Since surgery in July of 2006 I have literally not been able to drink at all. Unless I go insane and start pouring booze into my g-tube, I believe I’m reasonably safe. So consider this blog entry what AA calls a “12th step,” which means sharing the program with others. There’s a chance somebody will read this and take the steps toward sobriety.

The 1,400 + comments BEFORE his death indicate that he very likely did reach some folks, and his recent passing will surely add to the numbers who will read the essay. With AA’s admonition to “Keep an Open Mind”, I urge you to read Ebert’s blog. It is difficult to imagine any harm done by this exceeding the good.

Good or bad, right or wrong, the pathway for these anonymity breakers was forged many years ago by Mrs. Marty Mann. Time will tell if disaster is to befall us. Thus far, the sky is not falling.

As with many rules for living, language, once again, fails to contain complexity. Carefully crafted exceptions are crucial.

AA’s presence in mass media requires vigilance by its members “practicing” humility, one day at a time.

The ‘promoter instinct’ is powerful.

So is the idea that we know ‘what Bill intended’ or didn’t intend.

As is the conviction that times have changed and the ancient, almost 70 year old principles contained in the traditions are outmoded and irrelevant.

“The spiritual substance of anonymity is sacrifice. Because A.A.’s Twelve Traditions repeatedly ask us to give up personal desires for the common good, we realize that the sacrificial spirit – well symbolized by anonymity – is the foundation of them all.”(12×12, pg.184)

Recovery is big, a billion dollar business – it’s not suffering from lack of understanding about treating addiction. Revealing memoirs are high dollar best sellers. There’s a veritable flood of them.

Ebert’s mention of the tendency of celebrities to slip after announcing their membership still doesn’t address the ‘sacrifice’ or ‘humility’ aspect – the foundation principle.

Fascinating comment! I had never thought of it in terms of sacrifice before, and that new perspective seems helpful for me to associate with humility, checking my ego, etc. thanks for that!

This is an important discussion, a very personal matter and I very much enjoyed the blog post. Fellowships (such as AA) don’t have a “rule” about anonymity any more than it has rules about humility. It has Traditions, not borne of wisdom but resulting from bad experiences. The reason there isn’t a rule is that there will always be exceptions to what is otherwise a guiding principle.

AA’s Anonymity wallet card states that the number one reason for anonymity (which means never disclosing the membership of OTHERS) is to “serve as an example of recovery and thus stimulate active alcoholics to seek help… AA Traditions urge the member to maintain strict anonymity, for three reasons; (1) active alcoholics will shun any source of help which might reveal his or her identity. (2) Past events indicate that those alcoholics who seek public recognition as AA members may drink again. (3) Public attention and publicity for individual members of AA would invite self-serving competition and conflict over different personal views.

“Anonymity in public media guards the unity of AA members and preserves the attraction of the program for the millions who still need help.”

Spiritually or practically, the more “compelled” I might feel to break my anonymity, the more sober-second-thought might reveal the rashness of such a decision. Noting that many break their anonymity in the early stages of recovery, I remember that my decision-making was more reactive than mindful, more rationalizing than introspective, in my early years.

There is still a stigma about HIV, sexual-orientation, creed, addiction and mental health. The argument that outing oneself will break down these barriers has proven to be not true. Stigma transcends our admiration of celebrity everywhere but Hollywood. If all of us lived in Hollywood maybe anonymity would be outdated, but being as we don’t, I for one, will continue to honour my anonymity and certainly yours too.

I want to be just like Joe C. when I grow up!

Thanks for the post. Traditions 11 and 12 still ring true for me today, and I especially like Ebert’s quote, “AA is anonymous not because of shame but because of prudence; people who go public with their newly-found sobriety have an alarming tendency to relapse.” The “safety” I felt (albeit fragile) when I first came into the rooms was deeply rooted in anonymity. I approach disclosure with the same approach I would with any personal medical issue; it’s private. Gossip sucks and is best left for the immature and disrespectful.

Yes, thank you, Bob, for a most thoughtful and provocative article. I particularly like the discussion that emphasizes there are no hard and fast rules, that this is an area that is up to each individual to decide according to her or his own conscience.

Surely today we are not persuaded out of fear of stigma as was paramount in the early days of the AA’s founding. However, the choice to remain anonymous as a member of AA in press, radio and TV as a spiritual practice of humility still resonates very strongly for me.

I appreciate that on our AA Agnostica website we use our first name and the first initial of our last name only, as the issue of anonymity on the internet is currently being considered by our group conscience governance process.

“Group conscience governance process.” I am in pain, reading that. Please, Thomas.

Ha — you know I need a good editor !~!~!

No matter their degree of celebrity, a prospective member must be able to approach AA confident that their anonymity will be respected and that they will not be pressured to break their anonymity for the benefit of AA. While some choose to break their own anonymity early in sobriety, I think many prospects would not reach out for help if they felt AA’s motivation was to take advantage of their celebrity for promotional purposes. On the other hand I don’t have a real problem with Roger’s personal choice to break his anonymity late in his life after many years of sobriety. It’s clear to me that this would have been a personal choice and free of any pressure from AA.

What shifted my move to being anonymous was the fact that I, as a practicing alcoholic, was self-centered to the max and tried to revolve everything I read, saw or experienced as pertaining to me. I discovered that by being anonymous about my alcoholism and recovery I was helped with my self-centered thinking. So what that I am a recovering alcoholic. I was “one in a million” when I came into the rooms of AA but today I’m just 1 of 7 billion and believe me it is a lot more comfortable. I have other medical problems that could kill me but I don’t go around telling everyone about them. One of my jobs, as a recovered alcoholic, is to be there for those still practicing alcoholics who reach out for help. I also need to be responsible in my civic duties and in any other sphere I might travel. That is what sobriety is all about to me after my 20 years of irresponsible alcoholic living.

Great article, very insightful. Made me re-think the whole issue of anonymity. On the other hand, there is truth to the fact that anonymity does have spiritual benefit and that newcomers who break their anonymity do have a history of relapse. Still, your article causes me to remember that the the Traditions are not sacrosanct, that they were added years after the program was caste in the Big Book, and that rules and guidelines need to be updated from time to time. Even the Big Book itself cautions us not to be “bound by tradition and all sorts of fixed ideas”.

Thanks for highlighting this very interesting question.

I agree about the problems of newly sober celebrities spewing PR about their “new way of life” to Jay, Dave, Oprah, Ellen or one of the Jimmy’s. Our Traditions do nothing to stop these folks who in early sobriety are unlikely to either know, or care about AA’s policies. They are often following a script crafted by a press agent. Celebs with good long term sobriety on the other hand are respectfully silent.

Craig Ferguson’s ‘outing’ (semi) was masterful, and I think, no great threat to his sobriety. He made it very clear that 28 day rehabs do not ‘cure’ the problem.

It is an irony that our best celebrity members are muzzled, while newbies offer details about their AA participation, sometimes while drugged out or buzzed on booze.

My problem with the yellow card is this, in my area we have a well known ’13 Stepper’ who’s recent activities have even been brought up at intergroup (no name was mentioned but everyone knew who we were talking about).

This man is trying to use the yellow card as a shield to hide behind, I would appreciate opinions on this matter.

Although I have never seen the “yellow card”, I believe its purpose is sound.

Any Friendship Meeting hopefully may contain folks who are new to the idea of working on their alcoholism and need the protection of sharing in a confidential manner.

I endorse the principle of meetings being protected, although I’m particularly open-minded about calling myself an alcoholic because I’ve mastered my fear of saying so as an individual.