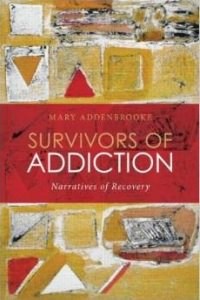

Survivors of Addiction

This is a review of the book Survivors of Addiction: Narratives of Recovery by Mary Addenbrooke. It was originally published in The Journal of Analytical Psychology, Volume 57, Issue 3, 2012.

This is an important book, crafted with great care, which builds much needed bridges between psychoanalysts, addiction counsellors and people in recovery from substance abuse. It is based on interviews and statements from fifteen men and women in treatment for alcohol or heroin addiction and followed over many years by the Substance Misuse Project at Crawley Hospital in England. Dr. Raj Rathod, a psychiatrist to whom the book is dedicated, saw many of these patients over time. The tenor of the book is captured in the preface: “We were all trainees at the hands of our patients as well as therapists to them”. The stories told by the recovering patients are linked together by succinct and valuable explanations of the processes of addiction and recovery by the author, a Jungian analyst. The inclusion of both alcohol and heroin misuse allows for a broad perspective on addictions.

This is a book about survivors. Only one of the subjects was still using drugs when interviewed, and his anger and defensiveness are in stark contrast to the tone of the other narratives. Some may think that the focus on long-term recovery is unrealistic, as many are unable to achieve this, but I find it a useful antidote to stereotypic assumptions that addicts are hopeless, and unsuitable candidates for therapies. With her experience of listening to clients and finding the vulnerability under their defences, Mary Addenbrooke reminds us not to be led astray by theories or suppositions. The book amplifies Jung’s statement that “Results may appear at almost any stage of the treatment, quite irrespective of the severity or duration of the illness”. (Jung 1953, para. 198).

In Part 1, “Lost in the Labyrinth of Addiction”, the narrators describe their memories of the depths of their addictions, speaking of despair, degradation, and the loss of all relationship to self and life. Several describe their experience of “using” as altering their entire constitutions. One man looked back on his experience of alcoholism as “being in the grip of something unspeakably evil” (p. 63). He feared he would die and the evil would stay with him. This theme is developed in David E. Schoen’s book, The War of the Gods in Addiction, where he states, “I believe it is this psychologically unintegratable aspect of addiction which I call Archetypal Shadow/Archetypal Evil, which distinguishes and makes alcoholism and addiction in some ways fundamentally different from most other mental/emotional disorders” (Schoen 2009, p. 92). The power of addiction is such that it interferes with all sense of relatedness. The active addict’s transference is to the object of the addiction, and it is necessary for the therapist to patiently wait for the client’s readiness to return to acknowledging the value of relationships with people.

Part 2 is on “The Turning Point”, the experience of deciding to stop using and the difficulties of following through. The narrators agree “stopping is just the start” (p. 84). They describe their extreme vulnerability, shame and suicidal feelings in early recovery, which may last as long as five to seven years. Not using may lead to feeling much worse than before, and all one’s limited energies must be focused on the moment-to-moment effort to stay sober. This is an experience of ego collapse at depth in which old ways of coping no longer work and it is necessary to build a new life and outlook piece by tiny piece. Jung’s words in his 1961 letter to Bill Wilson, a founder of Alcoholics Anonymous, resonate here: “I am strongly convinced that the evil principle prevailing in this world leads the unrecognized spiritual need into perdition if it is not counteracted by real religious insight, or by the protective wall of human community” (Jung 1976, p. 624). Most of the subjects turned to AA or NA in their urgent need for support and meaning. Even those who did not do so seemed to develop their own personal versions of a 12-step approach. I am convinced that there is an archetypal pattern underlying recovery.

Part 2 is on “The Turning Point”, the experience of deciding to stop using and the difficulties of following through. The narrators agree “stopping is just the start” (p. 84). They describe their extreme vulnerability, shame and suicidal feelings in early recovery, which may last as long as five to seven years. Not using may lead to feeling much worse than before, and all one’s limited energies must be focused on the moment-to-moment effort to stay sober. This is an experience of ego collapse at depth in which old ways of coping no longer work and it is necessary to build a new life and outlook piece by tiny piece. Jung’s words in his 1961 letter to Bill Wilson, a founder of Alcoholics Anonymous, resonate here: “I am strongly convinced that the evil principle prevailing in this world leads the unrecognized spiritual need into perdition if it is not counteracted by real religious insight, or by the protective wall of human community” (Jung 1976, p. 624). Most of the subjects turned to AA or NA in their urgent need for support and meaning. Even those who did not do so seemed to develop their own personal versions of a 12-step approach. I am convinced that there is an archetypal pattern underlying recovery.

Parts 3 and 4 describe the lifelong effort toward continued recovery, which is an individuation journey. In a letter to Dr. Rathod, a former heroin addict, Ben, speaks of the need for recovering people to find a “sense of themselves that is whole and entire” (p.164). He describes heroin as providing an unmatched sense of wholeness, but gave it up because of his fear of dying and the suffering this would cause other people. Over time he started to build what he calls “this intense relationship with life itself”. He found this through building connections to nature, the arts, family and “the numinous” (his word). All of the survivors of addiction spoke of the ongoing need to discover connections to life and meaning. Often their lives were simpler and seemed externally less successful than during the early years of addiction when their drug fuelled them. With an emphasis on authenticity, humility and spiritual connection, they were able to build lives of integrity. Several worked as drug counsellors and found this ‘giving back’ to be very helpful to their own ongoing recovery.

Mary Addenbrooke refers to some of the archetypal patterns underlying addictions as being that of “The Lost Child”, “The Negative Hero”, “The Wounded Healer” and “The Scapegoat”. Another powerful archetypal pattern described throughout this excellent book, but not named as such, is the archetype of transformation underlying recovery.

Whether in 12-step programmes or not, the survivors found that they had to go through the processes of letting go of the false self and the corrupted ego, facing the personal shadow, developing consciousness of the ego-self axis, and the return to give to others as a contributing member of the collective. David Schoen expands on these steps in his previously referenced book. These patterns are found in fairy tales and spiritual practices, as well as in psychoanalysis. Whether in addictions’ treatment, analysis or both, the recovering person will find him/herself to be guided by this powerful pattern of transformation. Mary Addenbrooke shows us that the psychoanalytic attitude can play an important role in the treatment of addictions.

A very interesting review, not only in its discussion of psychotherapeutic approaches to addiction recovery, but also in the way it presents a simple structure for the recovery process. There is an obvious parallel between the book’s outline and the AA template: “Our stories disclose in a general way what we used to be like [Part 1], what happened [Part 2], and what we are like now [Parts 3 & 4].” (BB page 58)

Nice one Roger. “(Rowland’s) craving for alcohol was the equivalent, on a low level, of the spiritual thirst of our being for wholeness…” (Jung’s letter to Bill W.) “AA’s 12 Steps are a group of principles, spiritual in their nature, which, if practiced as a way of life, can expel the obsession to drink and enable the sufferer to become happily and usefully whole.” (12+12 Foreword).

In “Survivors of Addiction” addicts tell how “it” – release into recovery – works; Addenbrooke, in her commentary on the narratives, and Schoen in The War of the Gods, seek to explain in the Jungian paradigm why the spiritual solution to addiction works; how we become integrated, or happily and usefully whole. Schoen says precisely, “The ‘why’ is what I want to address in this book, especially for skeptics, agnostics, and non-believers.”

Jung’s not for everyone but he “speaks to my condition”. Schoen notes,

As an agnostic I’m content that the Great Reality within me is that unsuspected inner resource which I could not access in my alcoholic madness.

So many books, so little time! On my list now. Thanks, Roger. The language of psychology helps me to make a little sense out of things, labeling experiences, creating terms to share those experiences with others, but for the most part the greater part of the unconscious “iceberg” remains unknown, thereby fitting my definition of agnostic: “I don’t know” and “the more I know, the more I know I don’t know”.

One theory I have is that the so-called greater portion of the iceberg/unconscious is made up of the exact same stuff as the tip of the iceberg/consciousness. So, for me, studying my conscious world, being present in the “tip of the iceberg” moment is all I need to know. I think the therapies and different formulations of the steps help to identify whether I am ‘underwater’ in past resentments and/or future fears, or in the here and now.